What exactly is international environmental governance?

International environmental governance establishes an international framework of policies and actions for governments, businesses, and society. This involves a broad range of stakeholders—governments, businesses, civil society, science, and local communities—ensuring diverse perspectives are heard and considered. Crucially, it facilitates the translation of global objectives into actionable national policies, while (ideally) providing support measures, like financial resources, capacity development, or technology transfer, and robust mechanisms for monitoring and compliance that enable and motivate stakeholders in achieving what they agreed upon. Furthermore, environmental governance fosters essential international cooperation, creating a platform for global dialogue and joint initiatives to address cross-border environmental challenges. It is instrumental for the successful implementation of Sustainable Consumption and Production (SCP) as envisioned in SDG 12. SCP emphasizes the provision of products and services and enabling of lifestyles that minimize environmental impacts while maximizing social and economic benefits.

Governance vs. Government: Clarifying the Distinction

One common point of confusion is the difference between “governance” and “government.” While government refers to a specific public body or group that runs a country, region, or city, governance is broader. It encompasses a wider spectrum of actors and focuses on the process of decision-making. This includes not only public actors and actions but also the roles played by various non-state actors such as the private sector, NGOs, local communities, and even science. In governance, governments are just one part of a wider network of actors that address a given challenge, such as plastic pollution. Governance is a more inclusive concept, recognizing that addressing environmental issues is an ongoing collaboration that is not the sole responsibility of governments but requires multiple stakeholders at different levels.

The Global Dimension of Environmental Governance

Globally, international environmental governance addresses issues that transcend borders and cannot be successfully managed by a single country or group of countries alone. It involves collaborative efforts to find common solutions and reach impactful agreements that wouldn't be feasible without transboundary cooperation. For example, the Paris Agreement on climate change is a significant milestone in global environmental governance. It unites nearly every country in the world, committing to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and combating global warming. As envisioned by the Paris Agreement, these initiatives should ideally include financial resources, capacity development, technology transfer, and robust monitoring and compliance measures, encouraging stakeholders to achieve their goals.

International environmental governance is a crucial endeavor to harmonize economic development with the planet's ecological boundaries. Over the past five decades, several important international agreements have emerged, primarily administered by the UN or its agencies, serving as the key institutions for global cooperation. In addition to the Paris Agreement (adopted in 2015), notable agreements include the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer (1987), the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal (1989), the Convention on Biological Diversity (1992), the Rotterdam Convention on the Prior Informed Consent Procedure for Certain Hazardous Chemicals and Pesticides in International Trade (1998), and the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (2001), among others. Each of these treaties and their subsequent processes represents a critical step toward global environmental stewardship.

Plastics – an international governance response to a global pollution problem

In Nairobi, negotiators from around the world convene for the third session of five in the "Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee" (INC-3). The primary focus of these negotiations is combating a global crisis - plastic pollution. Given its transboundary nature and widespread impact on ecosystems, a coordinated global response is essential. Globally, over 20% of plastic waste is mismanaged, equating to more than 20 million tons annually, which pollutes ecosystems and has detrimental effects on humans, animals, and plants. Less than 10% of plastic is recycled, with the majority either dumped or incinerated. Additionally, plastics often contain chemical additives harmful to human health and ecosystems.

In this context, recent discussions have highlighted three specific considerations that underscore the urgency and complexity of the plastics challenge:

Rethinking the Plastics Life-Cycle

In Nairobi, numerous governments and stakeholders are advocating for a comprehensive approach to tackle plastic pollution that considers the entire life cycle of plastics. Emphasizing the complexity of the issue necessitates essential initial steps, such as curbing plastic production. This can be achieved by phasing out specific types of highly polluting single-use plastics, like plastic bags—a crucial first step toward fostering sustainable production and consumption of plastics. Other straightforward measures include implementing pricing for plastic waste, incentivizing its proper collection.

However, it is evident that there is no one-size-fits-all solution, neither politically nor technologically. Instead, a combination of measures, actions, and technological solutions must address all stages in the life cycle of plastics. This may involve reducing plastic production through the implementation of a "cap" on new plastics, phasing out problematic single-use plastic products, promoting reuse, mandating increased recycled content in plastic products, and, as a last resort, improving plastic waste management for what remains.

Global (Producer) Responsibility

In Nairobi, numerous states and stakeholders are advocating for a paradigm shift, placing the responsibility for combating the global plastic pollution crisis squarely on the producers. This shift comes in response to the recognition that existing fragmented regulatory frameworks, as well as the self-regulation of producers, voluntary commitments, and localized initiatives, have proven insufficient. The evidence lies in the unabated growth of plastics production and pollution over the years.

The trajectory of plastic production has remained unbroken for the past 50 years and is, in fact, accelerating, with many plastic producers actively expanding their production capacities. The plastics industry, primarily derived from fossil materials such as oil and coal, has become highly lucrative, forming a powerful lobbying group. This financial interest exacerbates the problem at hand. Notably, many oil and gas-producing countries and businesses see plastics and chemicals as a promising avenue for continuing to exploit fossil fuels. This perspective is driven by the need to navigate increasing regulatory pressures from more stringent climate policies limiting the use of fossil fuels as energy sources.

Diverse concerns and diverse interests

Learn more: Policy Brief

In Nairobi, as in any international environmental negotiation, a collision of very diverse concerns and interests is evident. These differences manifest across and within continents, as well as between and within countries. Representatives from countries and businesses engaged in the exploitation of fossil fuels, plastics and chemicals production, and those exporting more plastic products than they import often perceive plastics as economically beneficial. Frequently, they overlook or outright ignore the environmental and health impacts associated with plastics. In Nairobi, these representatives typically strongly oppose measures aimed at reducing plastic production.

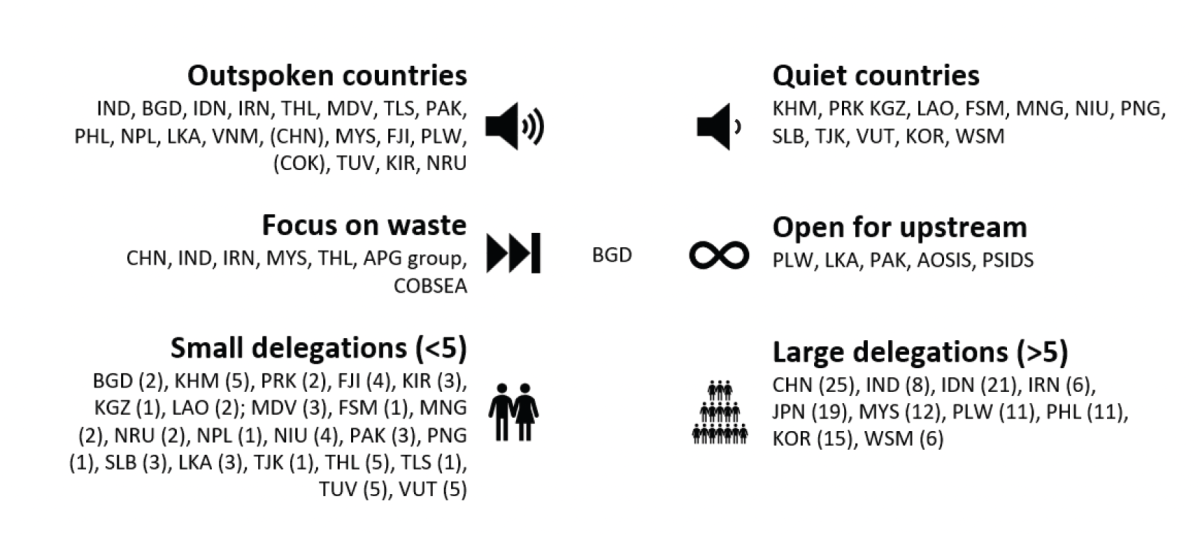

In contrast, representatives from countries that import plastic products and those concerned about the environmental and health effects of plastic pollution, as well as impacts on vital sectors like agriculture, fisheries, or tourism, generally support regulatory measures covering the entire life cycle of plastics. However, managing plastic waste and altering production patterns are complex issues, and solutions may be locally specific. In Asia, a region characterized by diverse economies, there is a significant divergence of opinion on the best approaches to tackling the plastics challenge.

The Way Forward

Similar to other environmental treaties, effective solutions for plastic pollution require a systems thinking approach. Recognizing that the gradual proliferation of plastics, especially in areas like food packaging, is facilitated by changing consumer habits and global trade is crucial. Redesigning these systems to reduce reliance on plastics and promote alternatives is essential. Solutions need to encompass a broader scope, including legislative actions, market frameworks, incentives for recycling, and encouragement of innovations. This holistic approach should also consider the environmental and health impacts of plastics, reflecting these considerations in their pricing.

As the world grapples with the plastics challenge at INC-3, it becomes evident that this is a crossroads similar to those faced during the negotiations of other environmental treaties. The lessons learned from these agreements, combined with a nuanced understanding of the current plastics challenge, will be instrumental in shaping a sustainable future by "closing the tap" on plastic pollution.

Source and Image credits: Breaking the Plastic Wave © 2020 The Pew Charitable Trusts.

Table: © 2023 EU SWITCH-Asia.